Is mental illness caused by our genes, our lifestyle, or both? What role do genes play in psychiatric disorders such as depression and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? Research into the genetics of psychiatric disorders could provide us with the answer.

But why would we care? Well, such discoveries can increase our understanding of the role our genes play in mental health and the biology behind these disorders. This can further help us improve the effectiveness of treatment and develop better diagnostics.

Role of Genetics in Psychiatry

Our genes can be seen as a recipe in a cookbook. Our genetic makeup contains information about important molecules – proteins – that make up our body and its cells. Genes are also relevant for psychiatric disorders. However, some people still believe that our own behavior and choices in life cause mental illness. After all, mental illnesses involve the brain, and our brain involves our own thoughts, consciousness, and emotions. This way of thinking is inaccurate. The brain is just as much a product of our genes as any other organ in the body. The functioning of the brain relies on brain cells. A disruption of proteins or pathways crucial for processes in these cells could alter how our brain functions. Research has identified genetic risk factors that can increase the chance to develop a psychiatric disorder. Moreover, genetic studies have found shared genetic risk factors across major psychiatric disorders (ADHD, bipolar disorder, depression).

As a neuroscience graduate student, I am interested to learn more about the biology behind mental disorders and what role psychiatric genetics could play in this.

The Environment and Our Genes

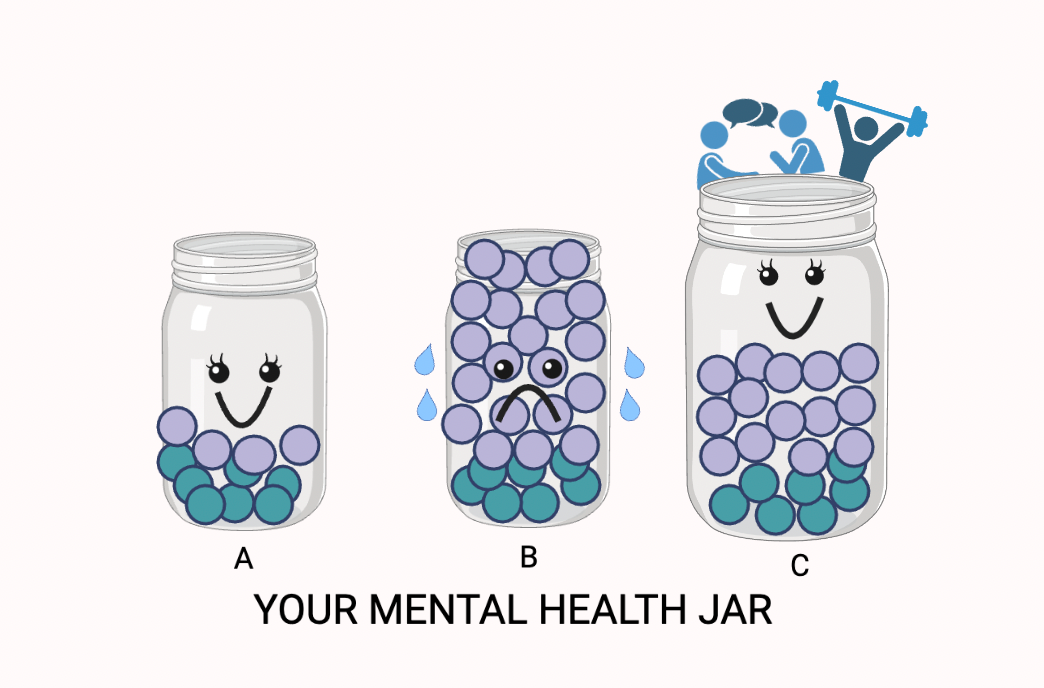

So, genes play a role in our mental health. But this is not the whole story. The environment also contributes to the development of psychiatric disorders. To better explain this complex interaction between our genes and our environment, I will refer to an analogy I recently heard during a talk from genetic counselor Dr. Jehannine Austin: our ‘mental health jar’. At the start of your life, the jar is filled with genetic factors (Figure 1A). We inherit these factors from our parents, such as the color of our eyes, but also our genetic vulnerability to develop a psychiatric disorder. Then throughout life, you get exposed to different life events and environments. Examples of environmental factors could be losing a job or dealing with family issues. These environmental factors further fill up the jar. When the jar is filled to the top and overflows, one can experience poor mental health (Figure 1B). The likelihood of the jar overflowing is determined both by how full the jar already was at birth, and the extent of environmental factors.

Luckily, it is possible to increase the size of the jar to avoid its overflowing (Figure 1C). Things such as a strong supportive social circle or our lifestyle (think of sleep, nutrition, exercise) can act as protective factors to keep the jar from overflowing. And when it does overflow, seeking medical or psychological help can also increase our jar.

Although no analogy is perfect, it does illustrate that genetic factors are not solely responsible for developing a mental illness. Furthermore, this shows us that taking care of ourselves and seeking help when needed is worth the effort for the sake of our mental health.

Looking Beyond Patients

Now that we are aware that both genes and the environment play a role in mental health, we want to better understand the mechanisms through which they exert this influence. One researcher working on this topic is Dr. Janita Bralten, junior group leader and researcher at the Department of Human Genetics at the Radboudumc. She is currently leading a project aiming to investigate genetic traits of mental health to increase our understanding of psychiatric disorders. Bralten describes the objective of the project as: ‘’Looking at the genetics of symptoms associated with psychiatric disorders such as ADHD and OCD [Obsessive Compulsive Disorder].’’

A novel aspect of Bralten’s research is that she doesn’t just focus on individuals with a psychiatric disorder diagnosis. Instead, she explores the continuum of ‘psychiatric traits’ that exist in the entire population. Such a trait is for instance ‘rigidity’ or ‘hyperactivity’ that every individual has more or less of. This way, we all lie somewhere on this spectrum of having more or less psychiatric-like symptoms, and this links to our genetic vulnerability for a mental disorder. The more traits you have, the higher your vulnerability. This means that to understand the genetics of psychiatric diseases, it is very interesting to study also those individuals who do not meet the diagnostic criteria of having a mental disorder.

For example: investigating differences in rigid behavior among people from the general population can help us better understand a psychiatric disorder such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). A trait such as rigidity shares genetic overlap with ASD meaning that we can learn more about the genetics and underlying biology of ASD by studying traits. Even the genetics of the trait sociability, how social we are, has been linked to ASD and other psychiatric disorders such as depression.

Moreover, this research could help us to identify subgroups of people that are more rigid or more hyperactive in regard to their symptoms. According to Bralten, looking at the spectrum of traits helps us to understand the diversity of symptoms in psychiatric disorders. The outcome of this research could help to improve diagnostics in psychiatry and help people to get the right diagnosis. The study has a ‘genetics-first approach’. Bralten: ‘’Analyzing involves putting together imaging traits from brain scans, outcomes from cognitive tests and symptoms to see what genetically clusters together to find a biological profile that is relevant for the clinic. I hope that this research line will give us ways to link someone to a personalized biological profile to then get to the next steps in treatment.’’

Future of Psychiatric Genetics

What next steps are needed in the field of psychiatric genetics? Future research studying psychiatric genetics requires not only large sample sizes to find genetic variance, but Bralten also emphasizes that current studies only include European populations: ‘’Everything we get out of the genetic studies is mostly tailored for European populations. We need larger samples that include different ethnicities to make sure that the findings are robust and generalizable to everyone’’.

Furthermore, this blog started with the fact that the genetics of mental disorders is complex and involves an interaction with the environment. Bralten: ‘’Psychiatric disorders are complex and not caused by just one gene, and therefore we can learn a lot more about the cause of the disorder.’’ The role of the environment is however very difficult to measure in genetic studies. ‘’The environment even includes the time when you were still in the womb,’’ said Bralten. This also emphasizes the relevance to include ways to measure environmental factors between individuals. Finding biological profiles for individuals can help us to say more about such individual differences regarding environmental factors. Bralten: ‘’I think we can improve the clinic by including underlying biology of psychiatric disorders and making biological profiles part of the clinic in the future.’’ Even if there is not one gene that causes a psychiatric disorder, we can still use genetics to personalize psychiatric healthcare by identifying more specific biological mechanisms and pathways.

All in all, psychiatric genetics remains a complex yet important topic to keep in mind when discussing mental health. Understanding the genetics of mental health could pave the way for better diagnostics and treatment – think of personalized treatment. Moreover, it shows that biological mechanisms underlie psychiatric disorders. Let this be a reminder to us all that having a mental illness is never our fault or choice.

References/ Further reading:

- Bralten, J., Mota, N.R., Klemann, C.J.H.M. et al. Genetic underpinnings of sociability in the general population. Neuropsychopharmacol. 46, 1627–1634 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01044-z

- Bralten, J., van Hulzen, K. J., Martens, M. B., Galesloot, T. E., Arias Vasquez, A., Kiemeney, L. A., Buitelaar, J. K., Muntjewerff, J. W., Franke, B., & Poelmans, G. (2018). Autism spectrum disorders and autistic traits share genetics and biology. Molecular psychiatry, 23(5), 1205–1212. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.98

- How to protect your mental health when genetics make you vulnerable. https://blogs.kcl.ac.uk/editlab/2019/11/26/how-to-protect-your-mental-health-when-genetics-make-you-vulnerable/

- Lotan, A., Fenckova, M., Bralten, J., Alttoa, A., Dixson, L., Williams, R. W., & van der Voet, M. (2014). Neuroinformatic analyses of common and distinct genetic components associated with major neuropsychiatric disorders. Frontiers in neuroscience, 8, 331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2014.00331